Do our color preferences impact the way we perceive the physical facts of the world?

According to research out of the Human Neuroscience Institute and recently published in the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports, the answer is yes.

We tend to think we perceive things, think about them and then decide whether we like them or not, but Professors of Human Development Adam K. Anderson and Eve De Rosa say our feelings are part of how we perceive our environment, so that even the perception of colors is related to how we feel about them.

“We are curious in a rigorous, neural way, if we can understand the reasons that people have different feelings about colors, different perceptions of them, and if we can find a biological reason for these color affects,” Anderson said. “The safest thing to say is that, yes, we find them in the brain, it’s biological, but biology is influenced by learning and culture.”

De Rosa and Anderson stressed the importance of understanding that biology and genetics are not the same, though they are commonly thought of as interchangeable. Brain biology can and does change in response to experiences, and thank goodness for that, otherwise we would be blank slates encountering everything as if for the first time over and over again.

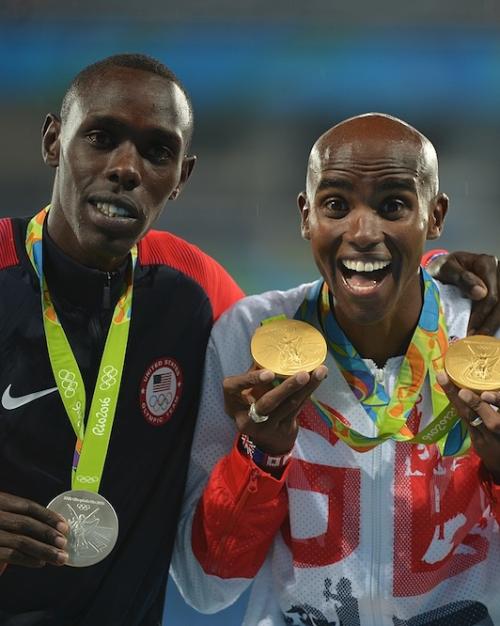

To study the brain’s affective response to color, Anderson, De Rosa, and Kesong Hu, a postdoc working with them at the time, conducted a two-part experiment. First, red or blue were paired with reward, earning participants a little bit of money, and then in a separate part of the experiment the colors were flashed on a screen and participants were asked which appeared first, without a reward attached.

Before these experiments, participants were asked to rate the positivity or negativity of red and blue, which told the researchers which color the participant preferred. They were also asked to fill out a questionnaire evaluating whether they were reward sensitive, punishment sensitive, both or neither.

“How people are oriented toward being reward sensitive is a powerful individual difference,” Anderson said. “How responsive are you to receiving reward? Does it influence your learning and behavior?”

At the group level, participants were more readily able to learn to associate blue with reward than red. This was particularly true of people who were more sensitive to rewards, but even the people who preferred red and were not reward sensitive learned to associate reward with blue more easily than with red.

“If you’re reward sensitive, it’s easier for you to associate winning money with blue and then, the kind of crazy thing is, it would influence your ability to see blue, how quickly you could see blue,” Anderson said.

De Rosa said this was her favorite part of the research data.

“Physically, the colors could come on the screen at exactly the same time, but if you like blue and it was associated with reward, you would say you saw blue first, which defies objective reality, defies what your eye is actually seeing,” she explained.

In other words, our feelings, motivations, personality and orientation toward the world shape how we perceive the physical facts of the world. And the colors we prefer reveal deeper biological predispositions to see the world in a particular way.

“At some point reality does break through,” De Rosa said, pointing out that the time delay between colors appearing on the screen was milliseconds. “It’s only when there’s nuance and ambiguity that expectations and beliefs can drive your perceptions.”

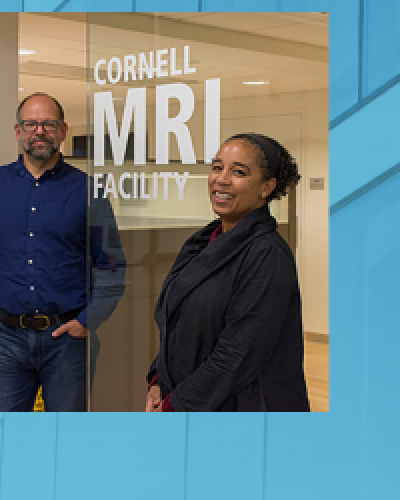

As part of their research, Anderson and De Rosa used fMRI to see the brains of research participants as they perceived blue and red. They found activity in the mesolimbic reward system (MRS), as well as the expected visual processing centers. The MRS is responsible for motivation and associative learning, and is one of the main ways the brain changes how it operates, remembers and perceives things. This suggests that color might be a way to intentionally change the way the brain behaves.

What does their research mean in the context of the widespread polarization of beliefs about the world and bitter disagreements about physical facts? What does it mean that our color preferences impact how we perceive the world? Are you a red or blue “person,” and what does that reveal about you?

“I think it’s important for people to understand that our views of the world can influence the basic facts of perception,” Anderson said. “The brain cuts corners, it thinks it learned something and then it over-applies it, which contributes to problems like stereotyping and racism. Appreciating this about the brain can give you pause before insisting on your account of reality, because perceptions really are subjective.”